7 Reduce dimensionality - UMAPs

Goals

- Build a ‘UMAP’ plot, so we can visualise celltypes and experimental information across all cells at a glance

7.1 Overview

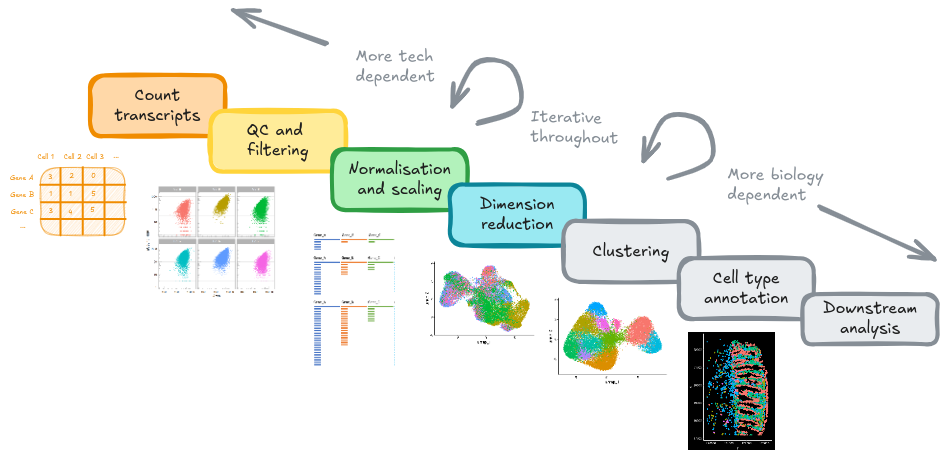

Before we dive into generating UMAP plots to visualise our spatial data we need to undertake a series of preprocessing steps. These steps are essential for transforming raw, high-dimensional data into a form that can be meaningfully interpreted.

Why are these steps needed?

- Normalisation Different cells have different total target counts. Normalisation allows them to be comparable.

-

Identification of highly variable features (feature selection) Identifying the most variable features allows retaining the real biological variability of the data and reduce noise in the data.

- Scaling the data: Highly expressed genes can overpower the signal of other less expressed genes with equal importance. Within the same cell the assumption is that the underlying RNA content is constant.

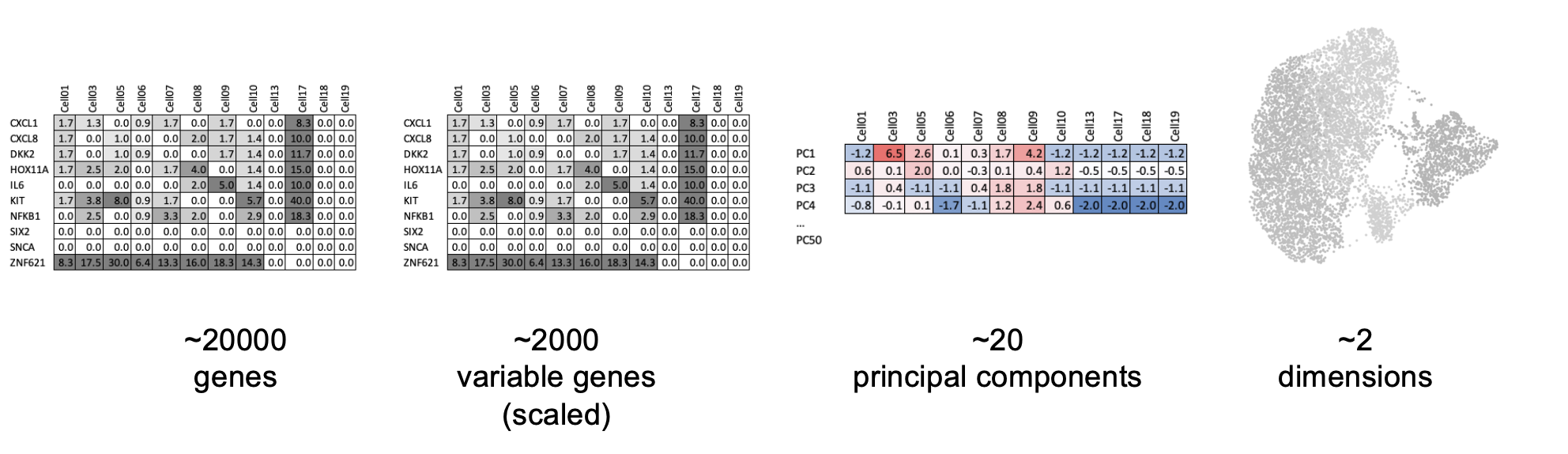

- Dimensionality reduction (PCA): Imagine each gene represents a dimension - or an axis on a plot. We could plot the expression of two genes with a simple scatter plot. But a genome or gene panel has 100s to 1000s of genes - how do you collate all the information from each of those genes in a way that allows you to visualise it in a 2 dimensional image. This is where dimensionality reduction comes in, we calculate meta-features that contains combinations of the variation of different genes. From hundreds of genes, we end up with 10s of meta-features

- Run non-linear dimensional reduction (UMAP): Finally, make the UMAP plot that arranges our cells in a logical and easy to visualise way. Note the tSNE algorithm (which makes tSNE plots) is an older alternative method to UMAP.

7.2 Reload data

To get started, lets launch a fresh R session, and load the libraries we need and the Seurat object form yesterday.

7.3 PCA

Our single-cell (spatial) RNA data is highly dimensional - even with only the 200 highly variable genes (which might be more than 200 in other experiments!). Dimension reduction with PCA is recommended for summarising data based on the most amount of variation (global differences). We will produce ‘principal component’ values to summarise expression in fewer dimension, and use these values in downstream analyses.

so <- RunPCA(so, features = VariableFeatures(so))Now there is a ‘pca’ reduction listed in the object.

so## An object of class Seurat

## 999 features across 56853 samples within 2 assays

## Active assay: RNA (980 features, 200 variable features)

## 13 layers present: counts.GSM7473682.HC.a, counts.GSM7473683.HC.b, counts.GSM7473684.HC.c, counts.GSM7473688.CD.a, counts.GSM7473689.CD.b, counts.GSM7473690.CD.c, data.GSM7473682.HC.a, data.GSM7473683.HC.b, data.GSM7473684.HC.c, data.GSM7473688.CD.a, data.GSM7473689.CD.b, data.GSM7473690.CD.c, scale.data

## 1 other assay present: negprobes

## 1 dimensional reduction calculated: pca

## 6 spatial fields of view present: GSM7473682.HC.a GSM7473683.HC.b GSM7473684.HC.c GSM7473688.CD.a GSM7473689.CD.b GSM7473690.CD.cBy peeking into the seurat object, we can see there is a value for each PC (Principal Component) for each cell.

so@reductions$pca@cell.embeddings[1:10,1:5]## PC_1 PC_2 PC_3 PC_4 PC_5

## HC_a_1_1 -6.148807 -2.0908949 -0.4825868 0.4346447 2.251673

## HC_a_2_1 -7.765302 -6.2518662 1.8308806 0.9827992 4.352795

## HC_a_3_1 -4.965210 0.4225925 0.2818806 -1.0218902 4.467894

## HC_a_4_1 -3.837060 1.6575017 0.4302138 -0.1013677 2.870886

## HC_a_5_1 -6.549506 -3.6873409 -0.1546158 0.5736327 4.347325

## HC_a_6_1 -6.059822 -7.1218463 1.3389979 0.2461749 3.405665

## HC_a_7_1 -5.609824 -2.5791504 0.4295388 1.1227985 4.756035

## HC_a_8_1 -7.076313 -4.6975718 -0.3541234 2.3167606 3.176212

## HC_a_9_1 -7.019115 -3.1431556 0.3734391 0.2201073 4.555789

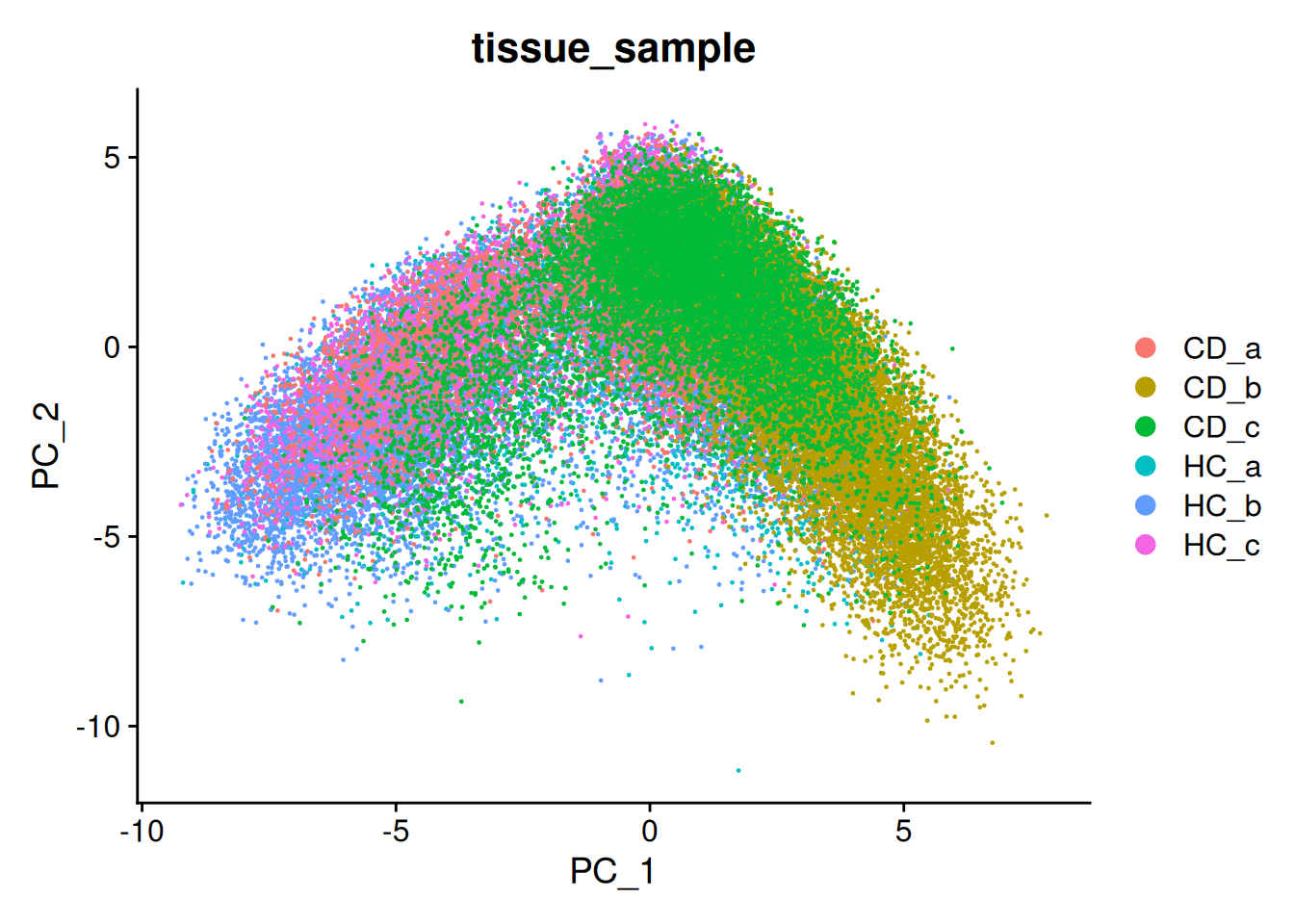

## HC_a_10_1 -6.518847 -3.6272531 -0.1846131 2.5870675 5.700536In some contexts (e.g. Bulk RNAseq experiments), PCs can be enough to group and explore the difference between samples. e.g. See this plot in some DEseq2 documentation.

We can try that here, but because of the sheer number of cells and the diversity among them, it rarely works in spatial or single cell datasets - simply a blob.

This is PC1 vs PC2.

DimPlot(so, reduction = "pca", group.by='tissue_sample')

7.4 UMAP

UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection) is a method for summarising multiple principal components into fewer dimensions for visualisation - generally just x and y.

UMAP is:

- Non-linear: Distances between cells in PCA are linear, whereas those in UMAP are non-linear. i.e. A larger distance between two cells does not necessarily mean a greater transcriptional difference.

- Non-deterministic: The same data could produce a different layout, though generally the functions use set random numbers avoid this. Even so - removing just one cell will shuffle the result, and it is a nearly impossible task to reproduce an existing UMAP! General trends should remain stable.

If you are interested in exploring how UMAP works further, this Understanding UMAP page is an excellent interactive resource. And for an in-depth discussion on how they can sometimes be misinterpreted see Biologists, stop putting UMAP plots in your papers.

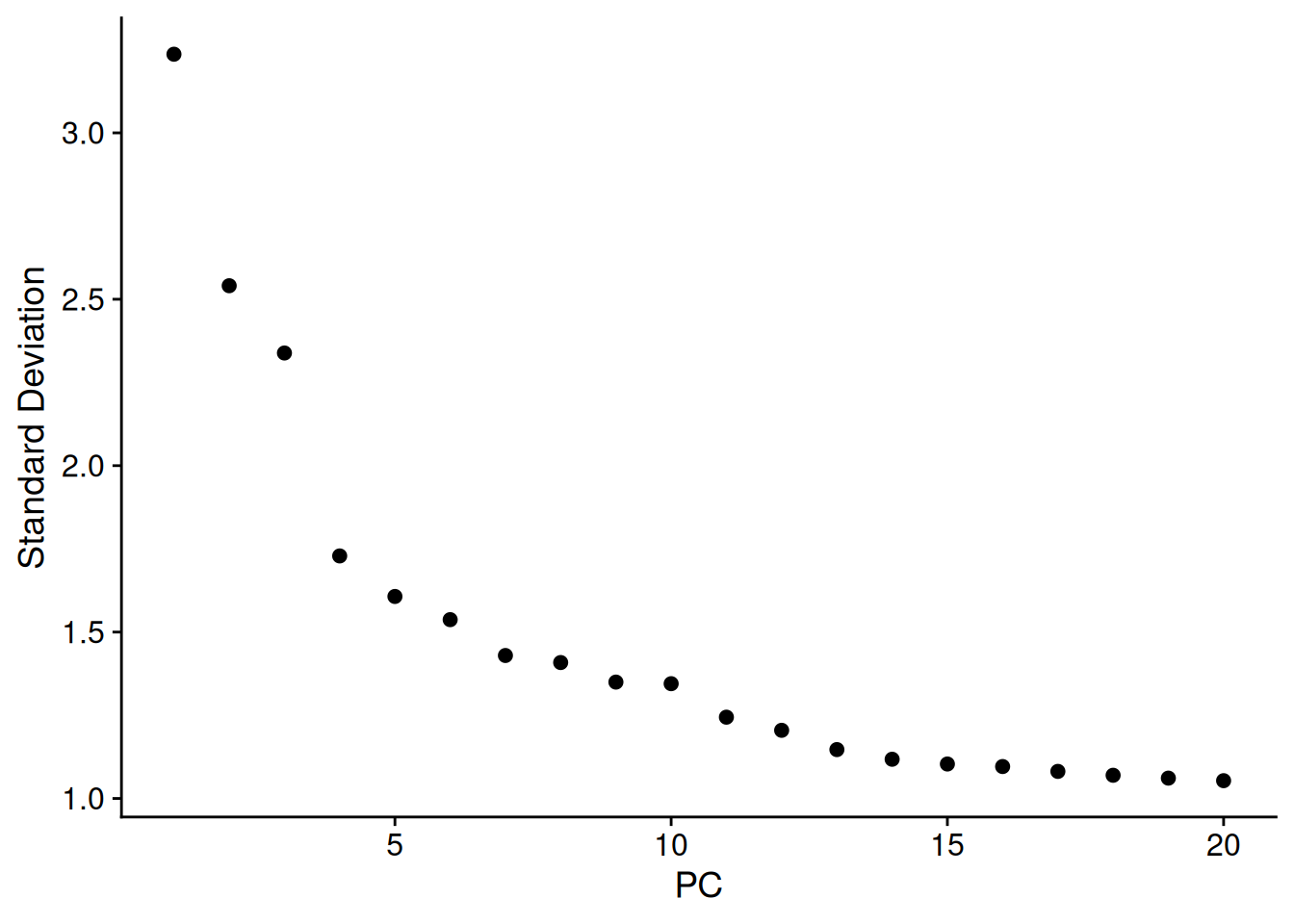

To build a UMAP we need to decide how many principal components we want to summarise. An ‘elbow plot’ shows the proportion of variance that is explained by each PC - starting from PC1 - which always explains the most. Eventually the variance explained drops off to a base level - extra PCs aren’t adding much there.

A general rule of thumb is to pick where the standard variation levels out in the plot below - the ‘elbow’. There is no harm in rounding up. Typically this is between 10-20, and is higher for more complex datasets.

Here we choose 15.

ElbowPlot(so)

Then build a UMAP with the first 15 PCs.

num_dims <- 15

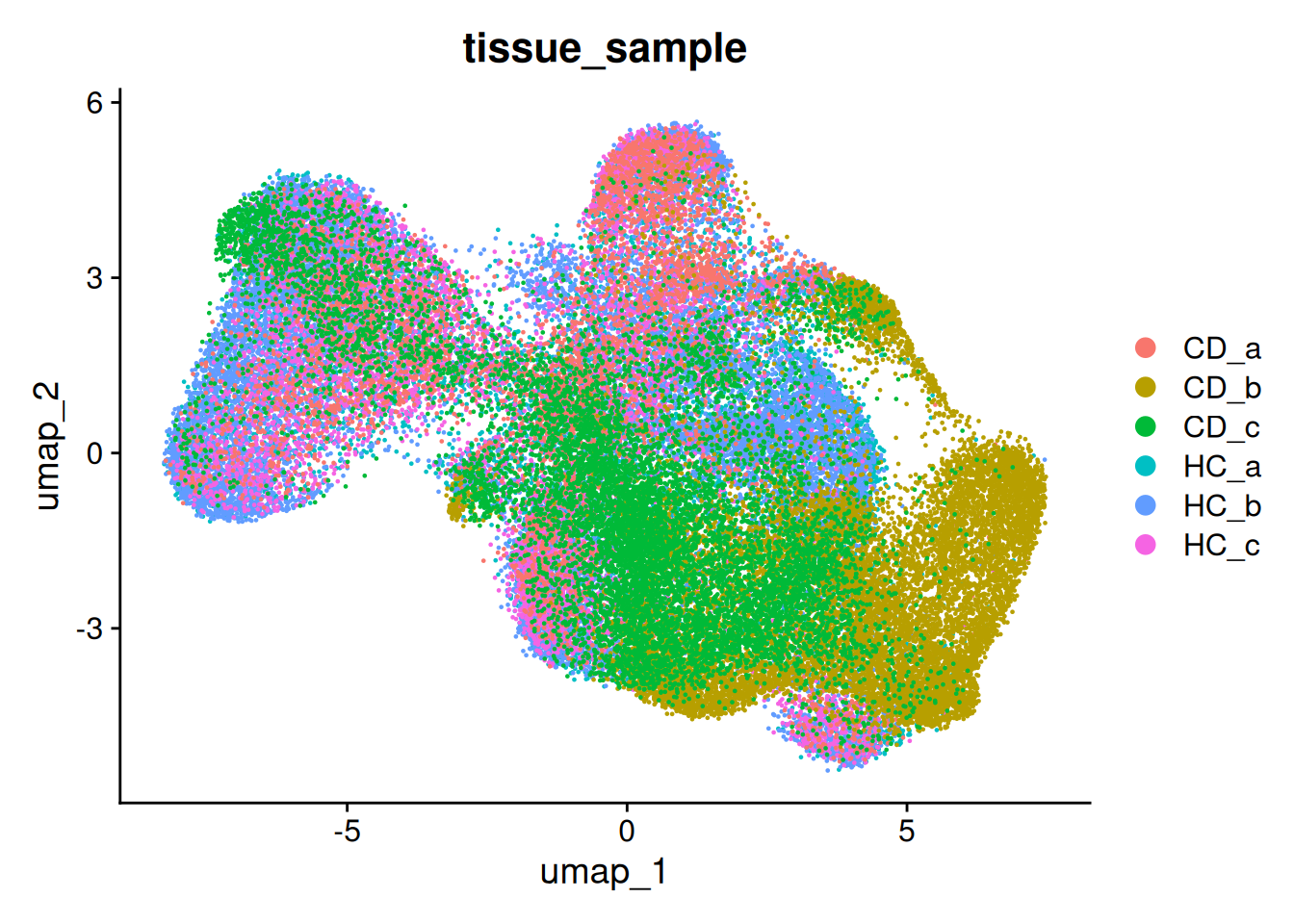

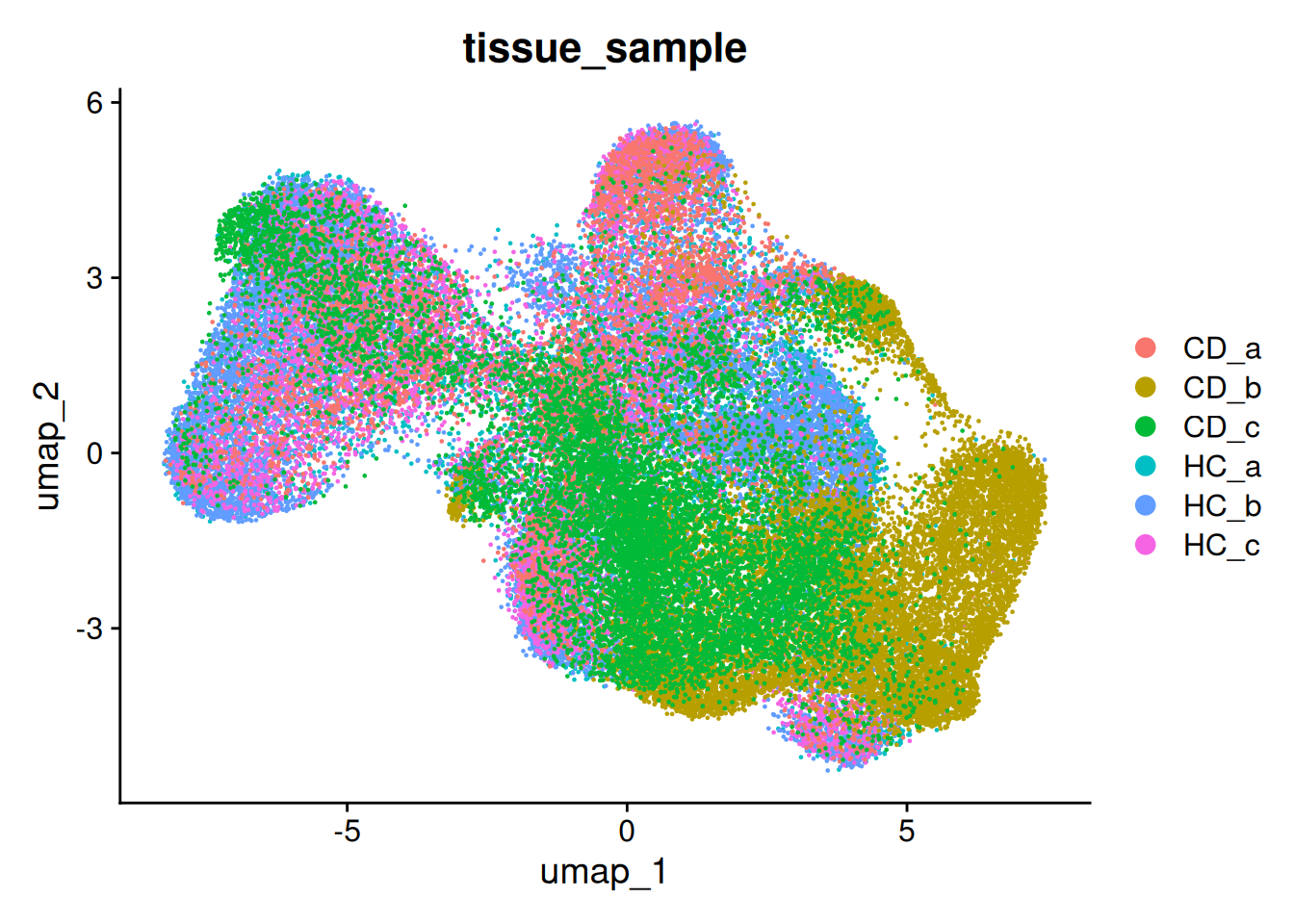

so <- RunUMAP(so, dims=1:num_dims)And plot it - Here coloured by the tissue sample.

# you can specify reduction='umap' explicitly

# DimPlot(so, group.by='tissue_sample', reduction = 'umap')

# But by default, if a umap exists in the object, Dimplot will plot it.

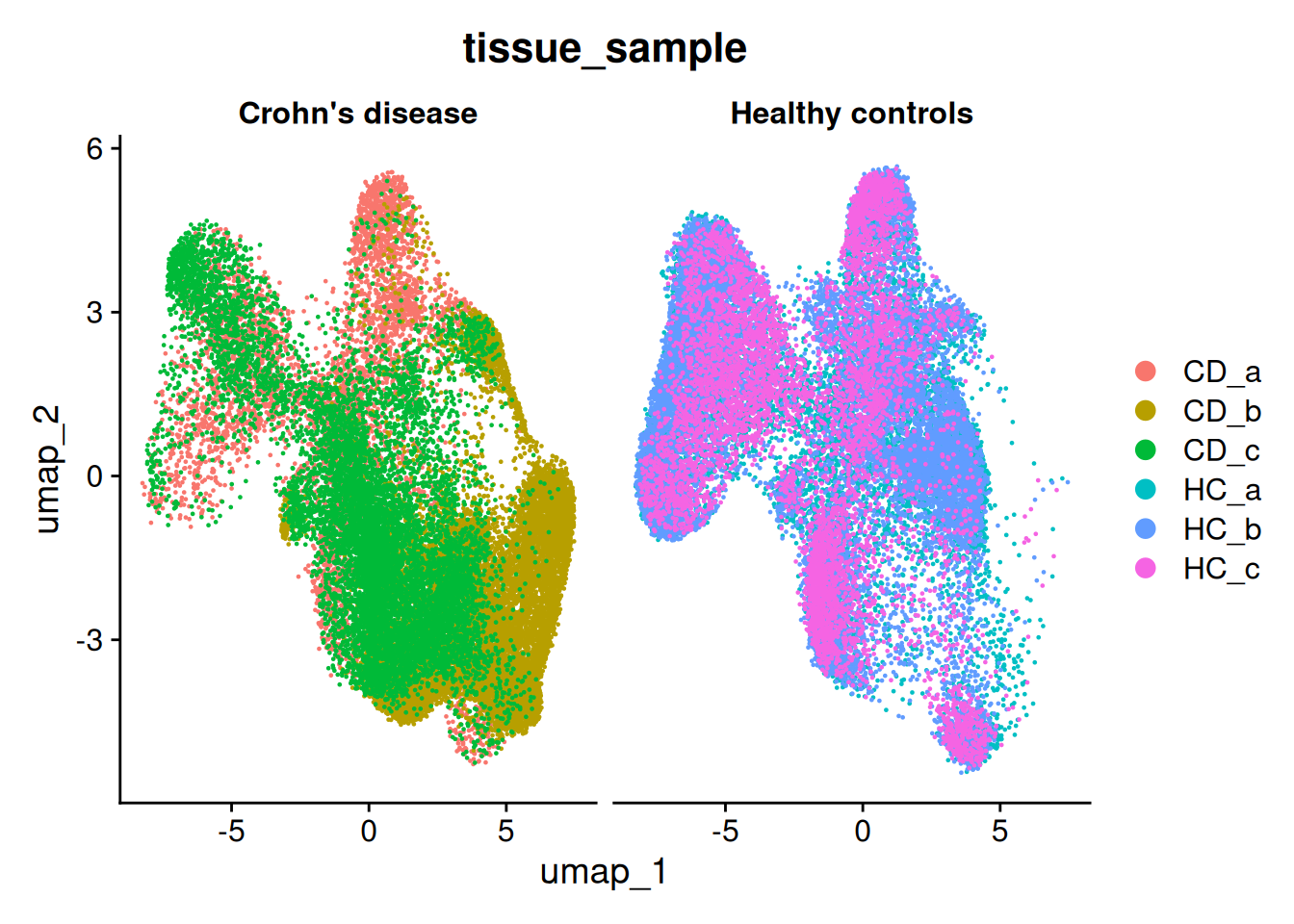

DimPlot(so, group.by='tissue_sample')

7.5 Using UMAP to visualise your data

Now is the time to plot any interesting looking metadata on your UMAP.

- QC : Slide, total RNA, negative probes, slide, batch

- Experimental: Groups, samples, timepoint, treatment, mouse

We want to identify trends and biases that could be technical or experimentally interesting.

View categorical factors with ‘DimPlot’, and continuous once with ‘FeaturePlot’. The split.by parameter is quite useful to separate out certain variables, like experimental group.

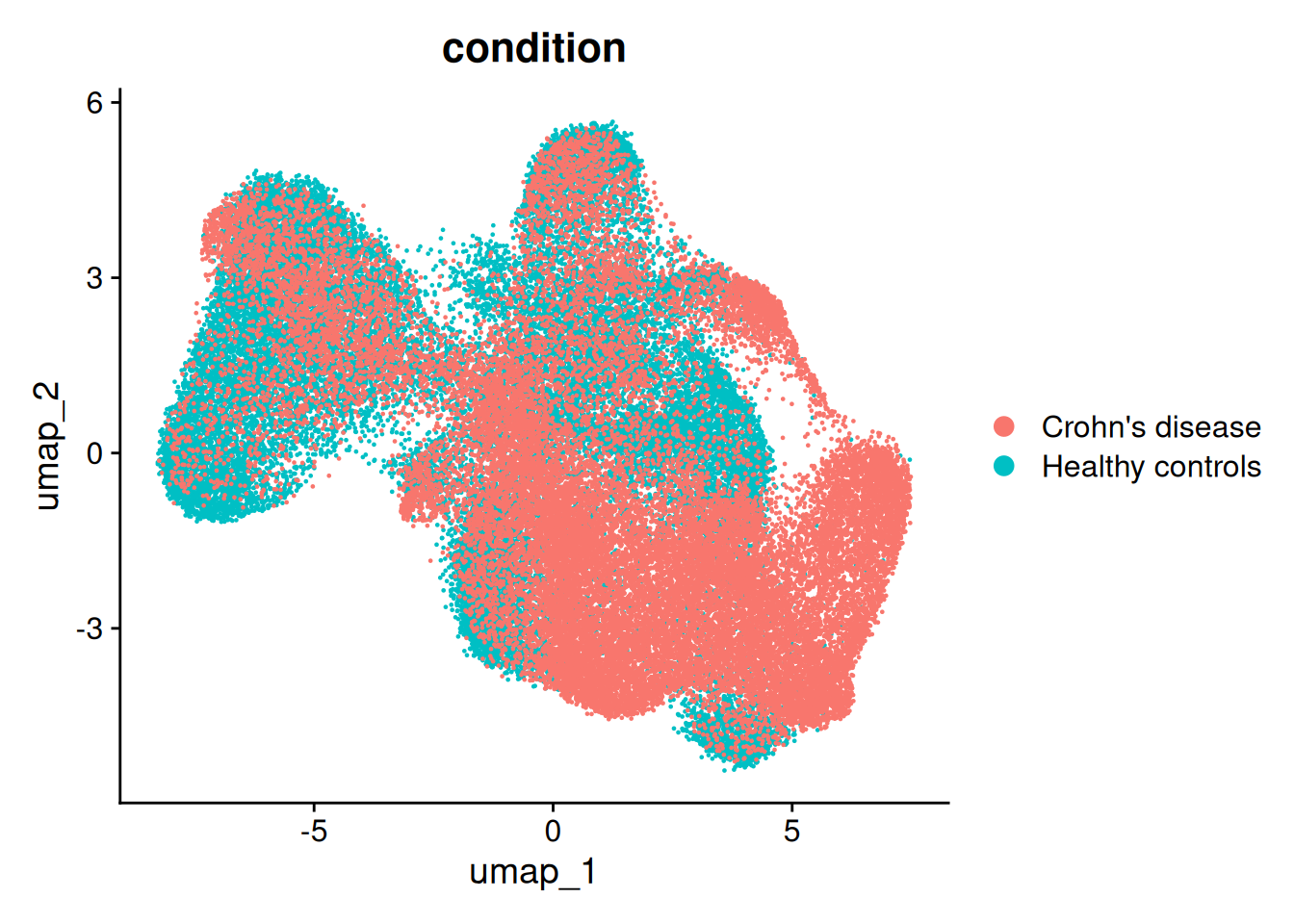

There is a little separation by condition - but it appears that it could be due to the individual (we’ll address this next).

DimPlot(so, group.by='tissue_sample')

DimPlot(so, group.by='condition')

DimPlot(so, group.by='tissue_sample', split.by='condition')

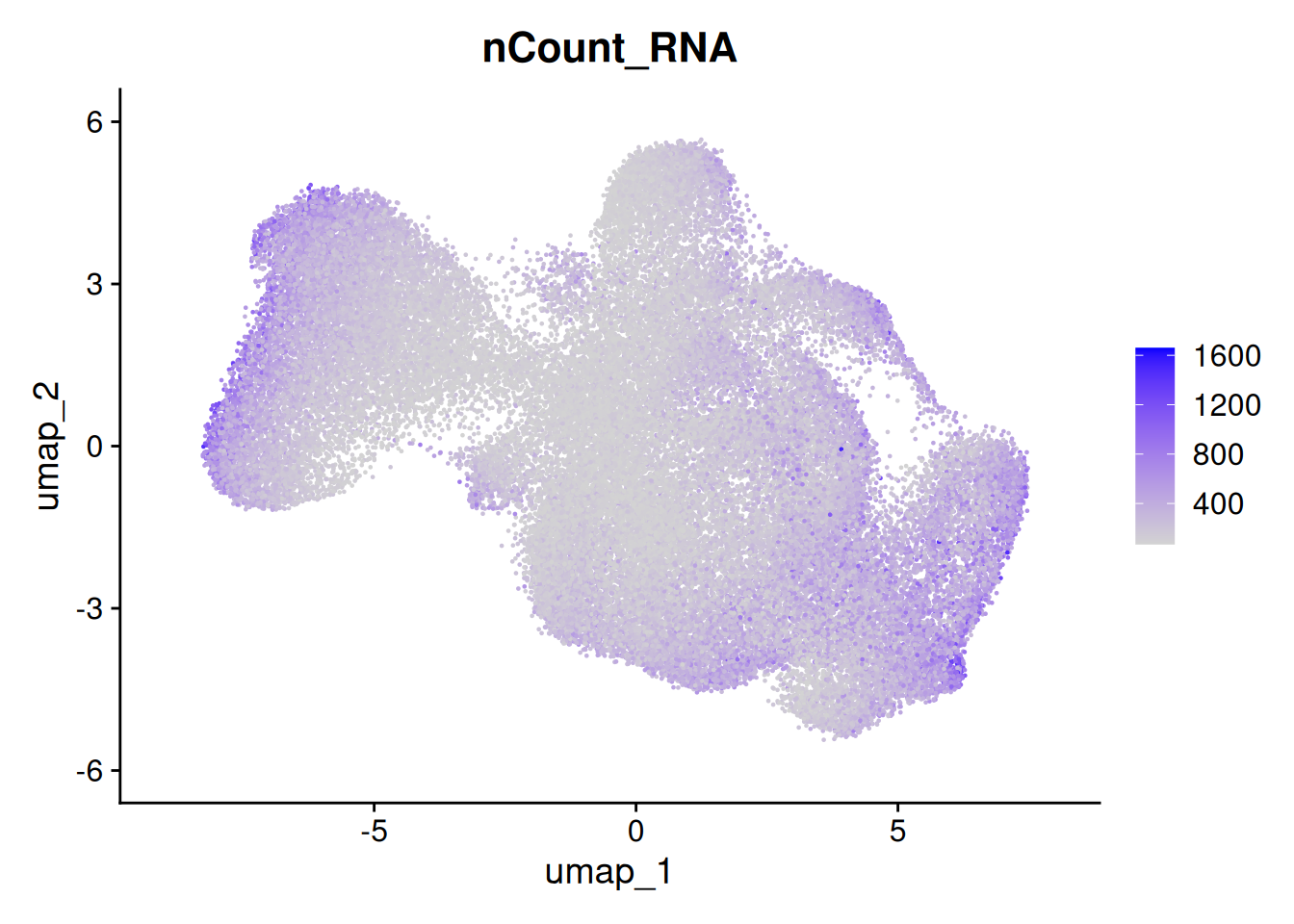

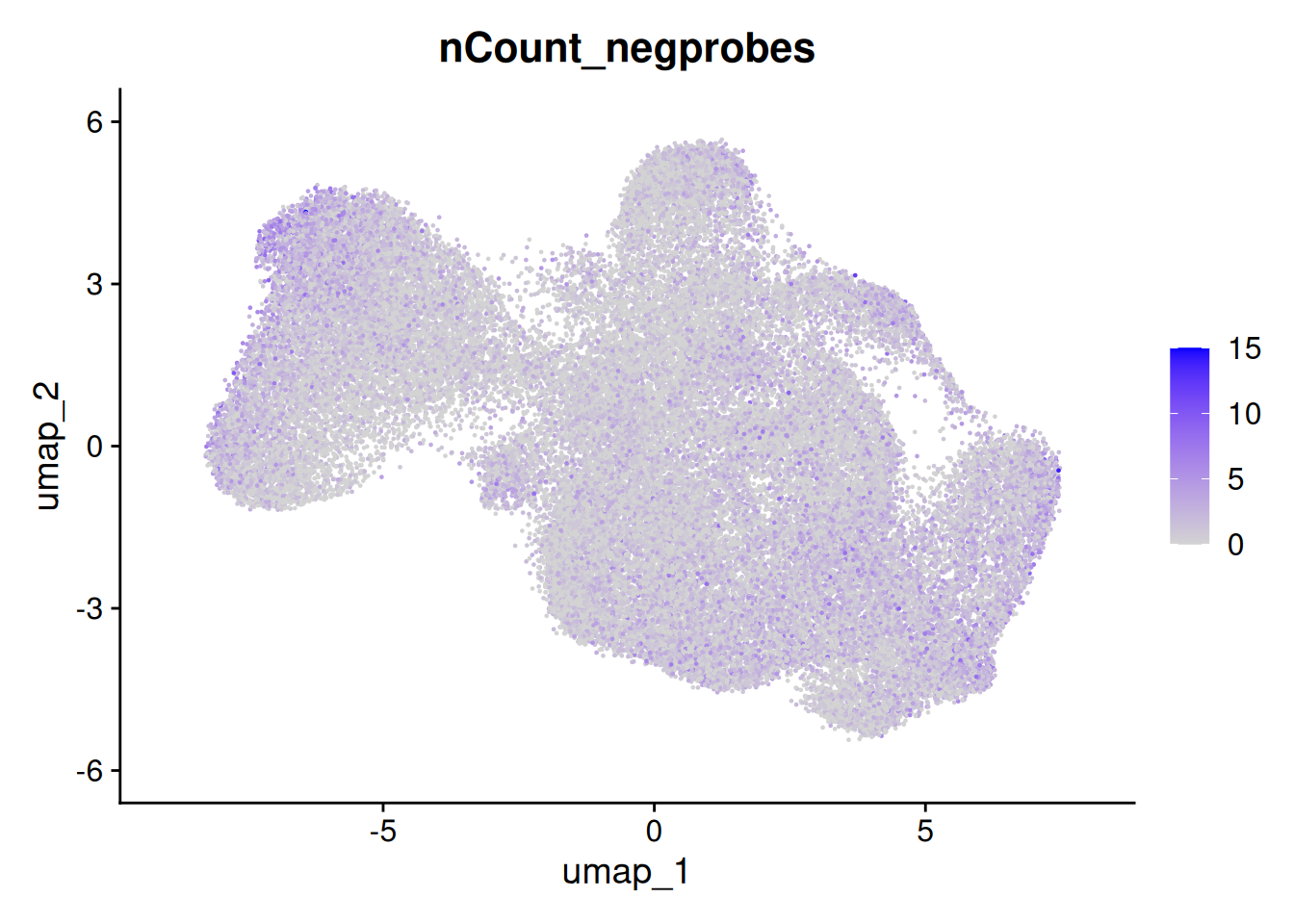

The metadata contains the number of total counts per cell (nCount_RNA) and total negative probe counts per cell (nCount_negprobes). Here we can see that the negative probe counts line up with our total counts. And that higher counts are concentrated in certain regions of the UMAP.

FeaturePlot(so, 'nCount_RNA')

FeaturePlot(so, 'nCount_negprobes')

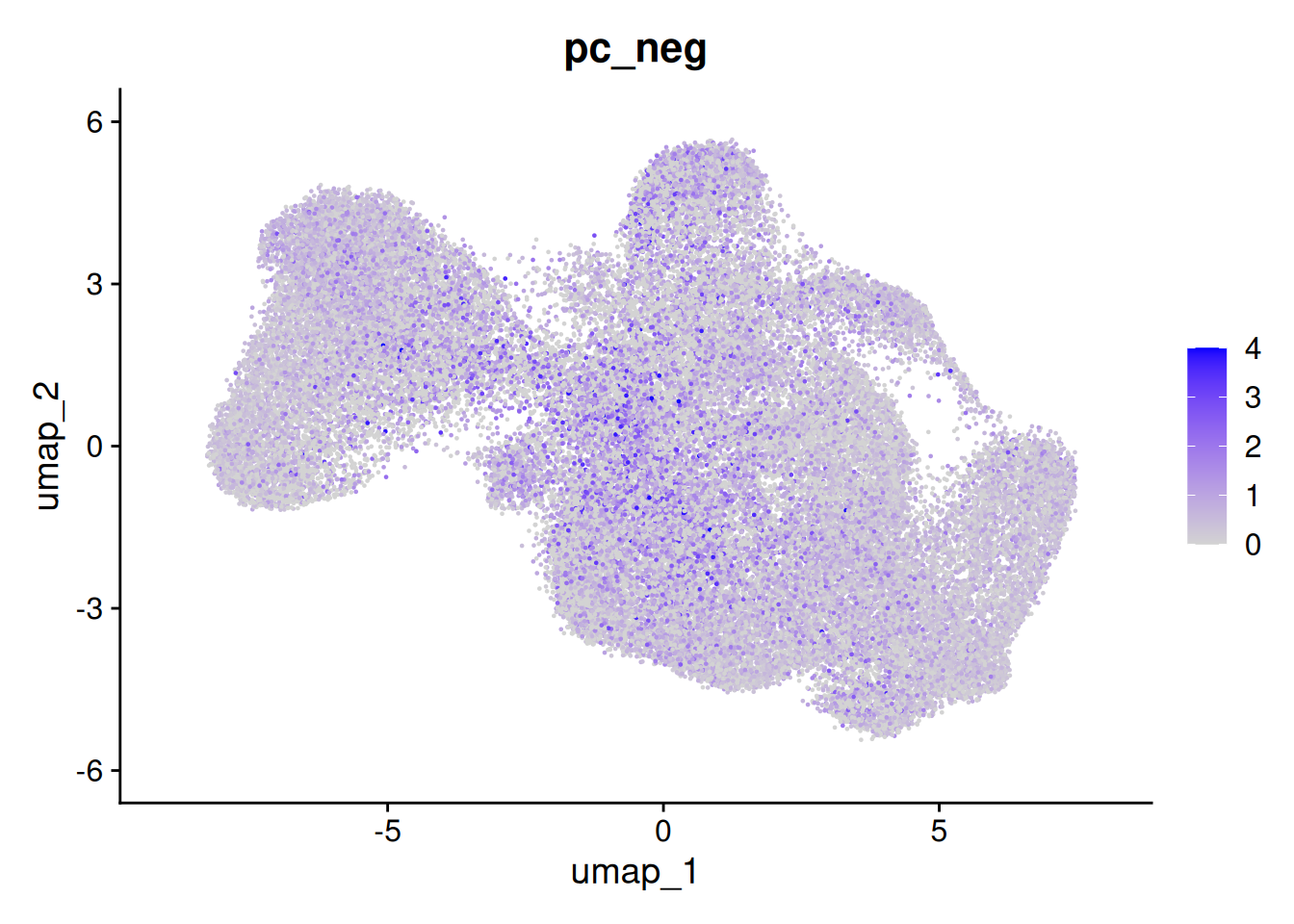

But the overall % of negative probes is more random.

so$pc_neg <- so$nCount_negprobes / (so$nCount_negprobes + so$nCount_RNA) * 100

FeaturePlot(so, 'pc_neg')

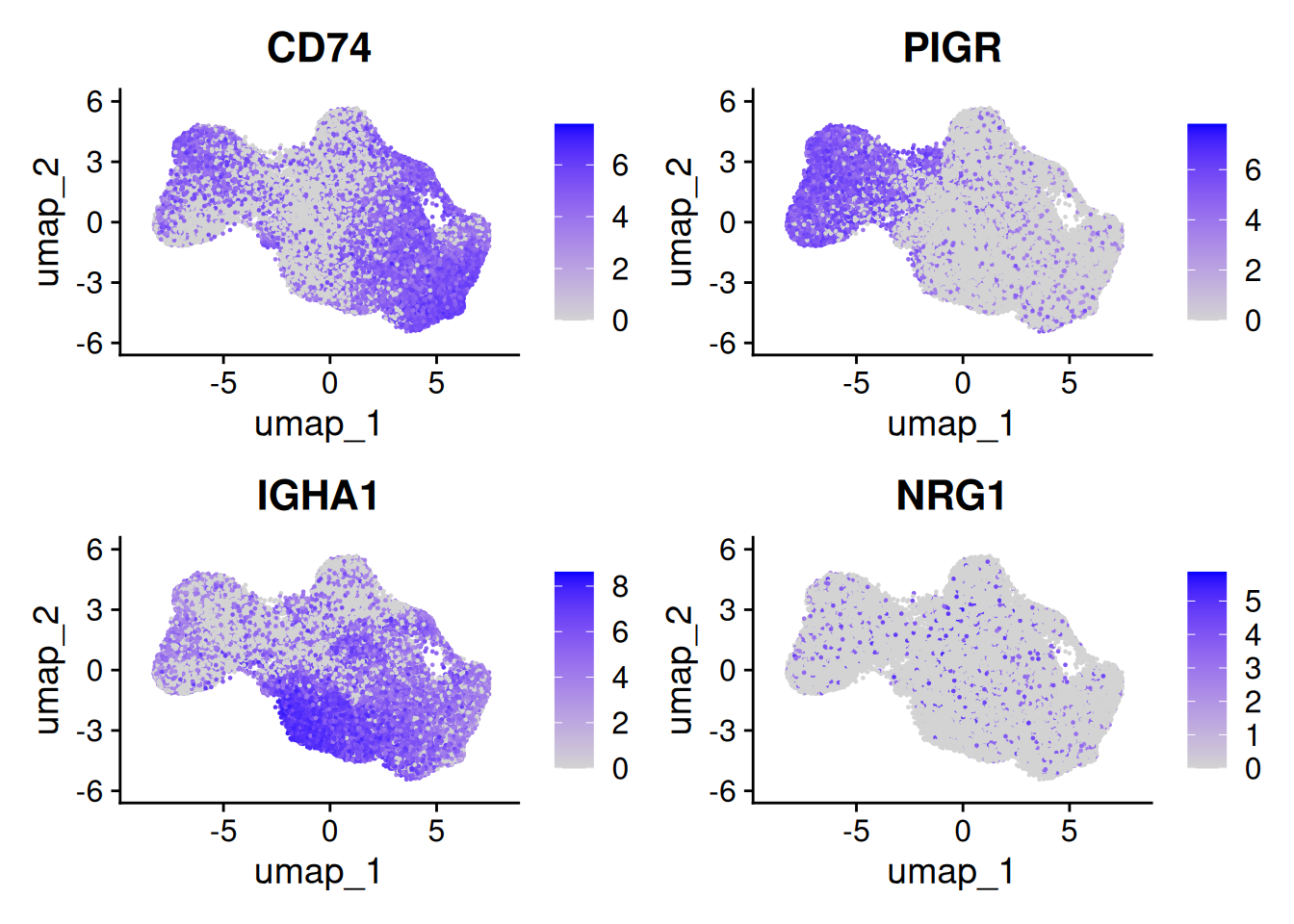

Likewise, it can also be helpful/fun to plot a few genes at this point.

We can provide a list of things we might think will be interesting or identify some cell types we expect to see. Here we show PIGR intestinal epithelial marker, CD74 and IGHA1 for their immune roles and NRG1 because it was discussed in the paper.

FeaturePlot(so, c('CD74','PIGR','IGHA1','NRG1'), ncol=2 )