Exploring History

Questions

- How can I identify old versions of files?

- How do I review my changes?

- How can I recover old versions of files?

Objectives

- Explain what the HEAD of a repository is and how to use it.

- Identify and use Git commit numbers.

- Compare various versions of tracked files.

- Restore old versions of files.

As we saw in the previous episode, we can refer to commits by their identifiers. You can refer to the most recent commit of the working directory by using the identifier HEAD.

We’ve been adding one line at a time to mean.py, so it’s easy to track our progress by looking, so let’s do that using our HEADs. Before we start, let’s make a change to mean.py, adding yet another line.

nano mean.py

cat mean.pyimport pandas as pd

dataframe = pd.read_csv("input.csv")

means = dataframe.mean()

# an ill-considered commentNow, let’s see what we get.

git diff HEAD mean.pydiff --git a/mean.py b/mean.py

index 67d0b5b..c9869a3 100644

--- a/mean.py

+++ b/mean.py

@@ -1,3 +1,4 @@

import pandas as pd

dataframe = pd.read_csv("input.csv")

means = dataframe.mean()

+# an ill-considered changeThis is the same as what you would get if you leave out HEAD (try it). The real goodness in all this is when you can refer to previous commits. We do that by adding ~1 (where “~” is “tilde”, pronounced [til-duh]) to refer to the commit one before HEAD.

git diff HEAD~1 mean.pyIf we want to see the differences between older commits we can use git diff again, but with the notation HEAD~1, HEAD~2, and so on, to refer to them:

git diff HEAD~2 mean.pydiff --git a/mean.py b/mean.py

index ffd919b..c9869a3 100644

--- a/mean.py

+++ b/mean.py

@@ -1 +1,4 @@

import pandas as pd

+dataframe = pd.read_csv("input.csv")

+means = dataframe.mean()

+# an ill-considered changeWe could also use git show which shows us what changes we made at an older commit as well as the commit message, rather than the differences between a commit and our working directory that we see by using git diff.

git show HEAD~2 mean.pycommit 3c865ca8570879e5ae8bbf3253283bf33d89bd14

Author: Mike Lynch <m.lynch@sydney.edu.au>

Date: Mon Oct 24 09:56:51 2022 +1100

Start a script to calculate the mean

diff --git a/mean.py b/mean.py

new file mode 100644

index 0000000..ffd919b

--- /dev/null

+++ b/mean.py

@@ -0,0 +1 @@

+import pandas as pdIn this way, we can build up a chain of commits. The most recent end of the chain is referred to as HEAD; we can refer to previous commits using the ~ notation, so HEAD~1 means “the previous commit”, while HEAD~123 goes back 123 commits from where we are now.

We can also refer to commits using those long strings of digits and letters that git log displays. These are unique IDs for the changes, and “unique” really does mean unique: every change to any set of files on any computer has a unique 40-character identifier. Our first commit was given the ID 3c865ca8570879e5ae8bbf3253283bf33d89bd14 so let’s try this:

git diff 3c865ca8570879e5ae8bbf3253283bf33d89bd14 mean.pydiff --git a/mean.py b/mean.py

index ffd919b..1da11d6 100644

--- a/mean.py

+++ b/mean.py

@@ -1 +1,4 @@

import pandas as pd

+dataframe = pd.read_csv("input.csv")

+means = dataframe.mean()

+# an ill-considered changeThat’s the right answer, but typing out random 40-character strings is annoying, so Git lets us use just the first few characters (typically seven for normal size projects):

git diff 3c865ca mean.pydiff --git a/mean.py b/mean.py

index ffd919b..1da11d6 100644

--- a/mean.py

+++ b/mean.py

@@ -1 +1,4 @@

import pandas as pd

+dataframe = pd.read_csv("input.csv")

+means = dataframe.mean()

+# an ill-considered changeAll right! So we can save changes to files and see what we’ve changed. Now, how can we restore older versions of things? Let’s suppose we change our mind about the last update to mean.py (the “ill-considered change”).

git status now tells us that the file has been changed, but those changes haven’t been staged:

git statusOn branch main

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: mean.py

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")We can put things back the way they were by using git checkout:

git checkout HEAD mean.pyUpdated 1 path from 37beb0dcat mean.pyimport pandas as pd

dataframe = pd.read_csv("input.csv")

means = dataframe.mean()As you might guess from its name, git checkout checks out (i.e., restores) an old version of a file. In this case, we’re telling Git that we want to recover the version of the file recorded in HEAD, which is the last saved commit. If we want to go back even further, we can use a commit identifier instead:

git checkout 3c865ca mean.pyUpdated 1 path from e79e40dcat mean.pyimport pandas as pdgit statusOn branch main

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

modified: mean.pyNotice that the changes are currently in the staging area. Again, we can put things back the way they were by using git checkout:

git checkout HEAD mean.pyAbove we used

git checkout 3c865ca mean.pyto revert mean.py to its state after the commit 3c865ca. But be careful! The command checkout has other important functionalities and Git will misunderstand your intentions if you are not accurate with the typing. For example, if you forget mean.py in the previous command:

git checkout 3c865caNote: switching to '3c865ca'.

You are in 'detached HEAD' state. You can look around, make experimental

changes and commit them, and you can discard any commits you make in this

state without impacting any branches by switching back to a branch.

If you want to create a new branch to retain commits you create, you may

do so (now or later) by using -c with the switch command. Example:

git switch -c <new-branch-name>

Or undo this operation with:

git switch -

Turn off this advice by setting config variable advice.detachedHead to false

HEAD is now at 3c865ca Start a script to calculate the meanThis might be one of the most alarming messages for git beginners: what it means is that HEAD, which normally points to the most recent commit of the current branch, has now been changed to point to a specific commit in your history. As the warning indicates, its main use is to be able to inspect an earlier commit.

To get things back to normal, reattach your HEAD with git checkout main.

It’s important to remember that we must use the commit number that identifies the state of the repository before the change we’re trying to undo. A common mistake is to use the number of the commit in which we made the change we’re trying to discard. In the example below, we want to retrieve the state from before the most recent commit (HEAD~1), which is commit f22b25e:

So, to put it all together, here’s how Git works in cartoon form:

If you read the output of git status carefully, you’ll see that it includes this hint:

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)git checkout without a version identifier restores files to the state saved in HEAD. The double dash -- is needed to separate the names of the files being recovered from the command itself: without it, Git would try to use the name of the file as the commit identifier.

The fact that files can be reverted one by one tends to change the way people organize their work. If everything is in one large document, it’s hard (but not impossible) to undo changes to the introduction without also undoing changes made later to the conclusion. If the introduction and conclusion are stored in separate files, on the other hand, moving backward and forward in time becomes much easier.

Challenge: Recovering Older Versions of a File

Alice has made changes to the Python script that she has been working on for weeks, and the modifications she made this morning “broke” the script and it no longer runs. She has spent ~ 1hr trying to fix it, with no luck…

Luckily, she has been keeping track of her project’s versions using Git! Which commands below will let her recover the last committed version of her Python script called data_cruncher.py?

git checkout HEADgit checkout HEAD data_cruncher.pygit checkout HEAD~1 data_cruncher.pygit checkout <unique ID of last commit> data_cruncher.py- Both 2 and 4

Solution

The answer is 5. Both 2 and 4.

The checkout command restores files from the repository, overwriting the files in your working directory. Answers 2 and 4 both restore the latest version in the repository of the file data_cruncher.py. Answer 2 uses HEAD to indicate the latest, whereas answer 4 uses the unique ID of the last commit, which is what HEAD means.

Answer 3 gets the version of data_cruncher.py from the commit before HEAD, which is NOT what we wanted.

git checkout will restore all files in the current directory (and all directories below it) to their state at the commit specified. This command will restore data_cruncher.py to the latest commit version, but it will also restore any other files that are changed to that version, erasing any changes you may have made to those files! As discussed above, you are left in a detached HEAD state, and you don’t want to be there.

Challenge: Reverting a Commit

Alice is collaborating with colleagues on her Python script. She realizes her last commit to the project’s repository contained an error, and wants to undo it. Alice wants to undo correctly so everyone in the project’s repository gets the correct change. The command git revert [erroneous commit ID] will create a new commit that reverses the erroneous commit.

The command git revert is different from git checkout [commit ID] because git checkout returns the files not yet committed within the local repository to a previous state, whereas git revert reverses changes committed to the local and project repositories.

Below are the right steps and explanations for Alice to use git revert, what is the missing command?

________ # Look at the git history of the project to find the commit ID- Copy the ID (the first few characters of the ID, e.g. 0b1d055).

git revert [commit ID]- Type in the new commit message.

- Save and close

Solution

The command git log lists project history with commit IDs.

The command git show HEAD shows changes made at the latest commit, and lists the commit ID; however, Alice should double-check that it is the correct commit, and no one else has committed changes to the repository.

Challenge: Understanding Workflow and History

What is the output of the last command in

cd means

echo "This is a script to calculate means" > doc.txt

git add doc.txt

echo "It is a work in progress" >> doc.txt

git commit -m "Started some documentation"

git checkout HEAD doc.txt

cat doc.txtIt is a work in progressThis is a script to calculate meansThis is a script to calculate means It is a work in progressError because you have changed doc.txt without committing the changes

Solution

The answer is 2.

The command git add doc.txt places the current version of doc.txt into the staging area. The changes to the file from the second echo command are only applied to the working copy, not the version in the staging area.

So, when git commit -m "Started some documentation" is executed, the version of doc.txt committed to the repository is the one from the staging area and has only one line.

At this time, the working copy still has the second line (and git status will show that the file is modified). However, git checkout HEAD doc.txt replaces the working copy with the most recently committed version of doc.txt.

So, cat doc.txt will output

This is a script to calculate meansChallenge: Checking Understanding of git diff

Consider this command:

git diff HEAD~9 mean.py. What do you predict this command will do if you execute it? What happens when you do execute it? Why?Try another command,

git diff [ID] mean.py, where [ID] is replaced with the unique identifier for your most recent commit. What do you think will happen, and what does happen?

Solution

TODO FIXME: this needs a solution!

Getting Rid of Staged Changes

git checkout can be used to restore a previous commit when unstaged changes have been made, but will it also work for changes that have been staged but not committed? Make a change to mean.py, add that change, and use git checkout to see if you can remove your change.

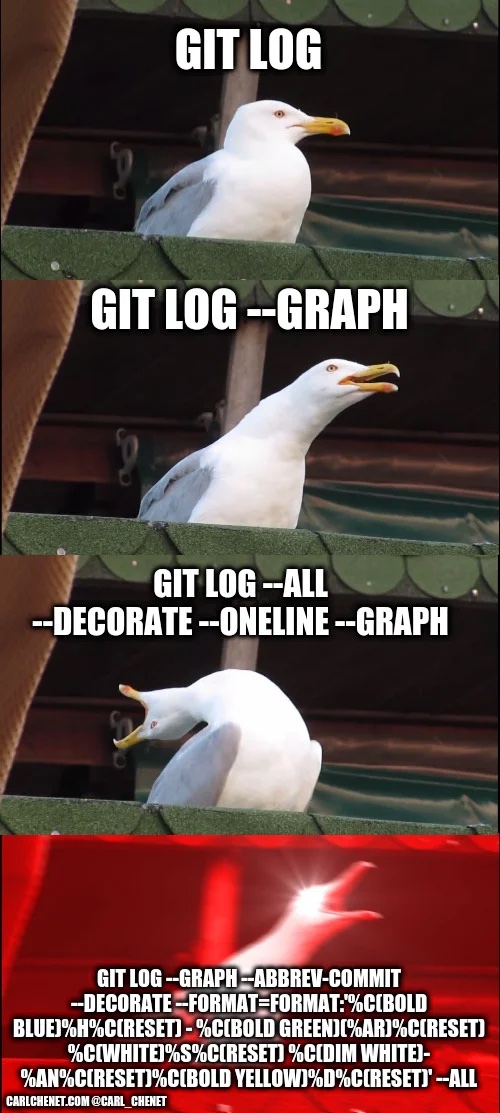

Explore and Summarize Histories

Exploring history is an important part of Git, and often it is a challenge to find the right commit ID, especially if the commit is from several months ago.

Imagine the means project has more than 50 files. You would like to find a commit that modifies some specific text in mean.py. When you type git log, a very long list appeared. How can you narrow down the search?

Recall that the git diff command allows us to explore one specific file, e.g., git diff mean.py. We can apply a similar idea here.

git log mean.pyUnfortunately some of these commit messages are very ambiguous, e.g., update files. How can you search through these files?

Both git diff and git log are very useful and they summarize a different part of the history for you.

Is it possible to combine both? Let’s try the following:

git log --patch mean.pyYou should get a long list of output, and you should be able to see both commit messages and the difference between each commit.

Question: What does the following command do?

git log --patch HEAD~9 *.txtKey Points

git diffdisplays differences between commits.git checkoutrecovers old versions of files.

All materials copyright Sydney Informatics Hub, University of Sydney